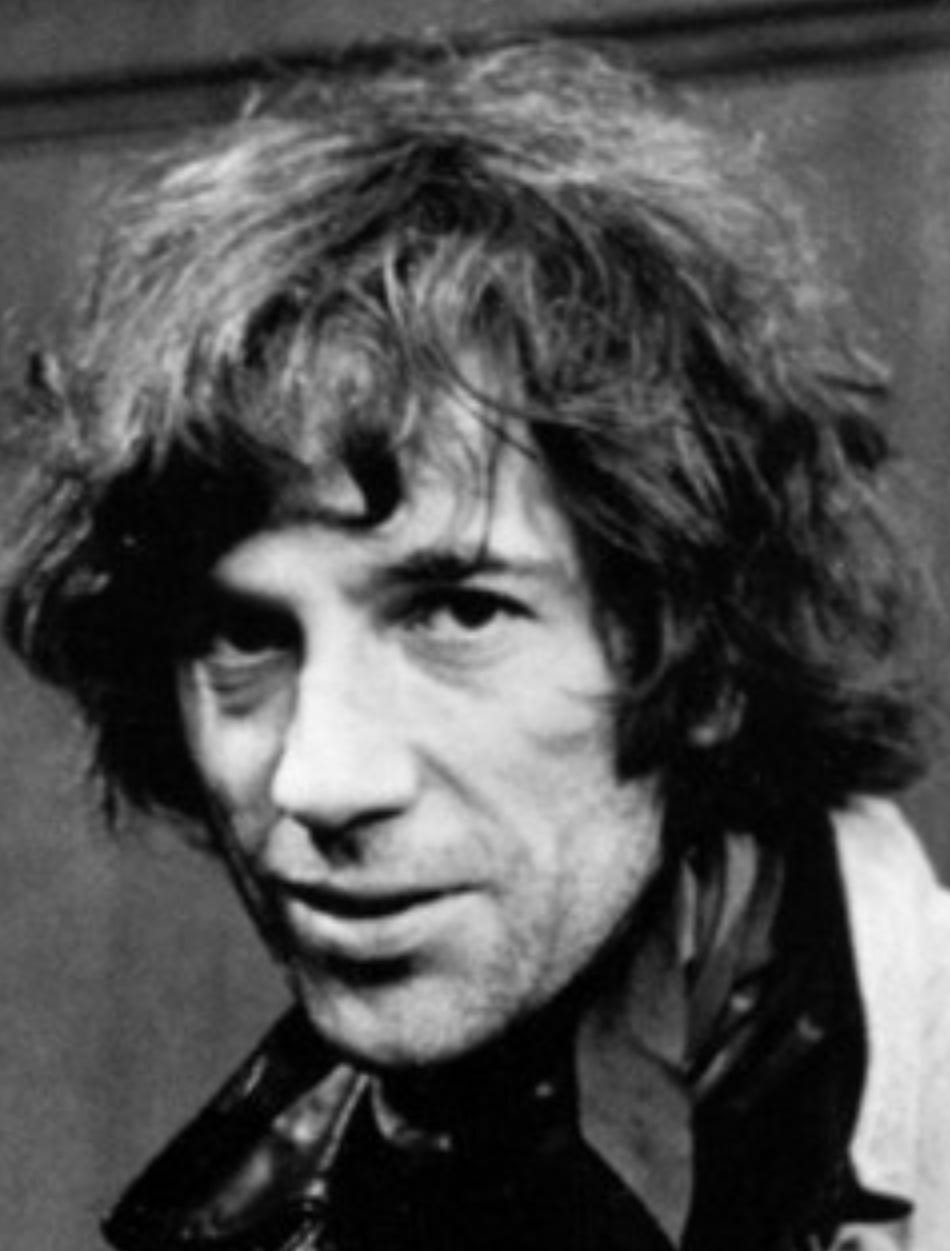

Donald Cammell – Rock ‘N’ Roll Filmmaker

The Scottish painter-turned-film director who lived one of cinema’s more unlikely lives.

On the face of it, director Donald Cammell was a failure. Just four movies completed in a career spanning 25 years – one wouldn’t be surprised to find the Scotsman relegated to the footnotes of film history. But as there was nothing unremarkable about the few pictures he completed, so Cammell’s extreme approach to existence makes his short, dramatic life impossible to ignore.

Born in Edinburgh in 1934, Donald Seaton Cammell’s early years were shaped by his eccentric father Charles. Young Don’s childhood was leant a particularly strange air by his old man’s role as the biographer of Aleister Crowley, the diabolist who reveled in his reputation as ‘the most evil man in the universe’. In later years, Cammell Jr would talk about the time he sat upon the knee of ‘The Great Beast’, an anecdote that was of particular interest to his friend Kenneth Anger, a man whose keen interest in the occult led him to place curses upon Rolling Stone Brian Jones and anyone else who dared to cross him.

Although a successful society painter by his mid-twenties, Cammell’s hopes for a respectable life were scuttled by his twin enthusiasms for film and the 1960s. A man who’d have listed hallucinogens and threesomes under his hobbies had he appeared in Who’s Who, his early attempts as a screenwriter left him convinced that, were he to have any control over the stories he wanted to tell, he would have to direct. So it was that, in collaboration with the acclaimed cinematographer Nicolas Roeg, Cammell created Performance, a film about bisexual gangsters, washed-up rock stars and drugs, lots and lots of drugs.

If all this wasn’t exciting enough, Cammell had convinced his good friend Mick Jagger to take on the role of retired musician Turner. The involvement of the world’s biggest rock star ensured there was no end of interest in Performance. But if audiences were expecting something along the lines of A Hard Day’s Night, they would come away equal parts baffled and troubled. An extraordinary film with fascinating things to say about sex and identity, Performance shook up people to such an extent, the producers shelved the picture for two whole years.

Eventually unleashed in 1970, Performance rapidly became a cult phenomenon. And as its reputation grew, so Donald Cammell found himself relocating to Hollywood. While in LA, he wrote a host of screenplays, became good friends with Marlon Brando (in keeping with his bizarre existence, Cammell first met the Method king while Marlon was in hospital being treated for scalded testicles) and struggled to find directing gigs worthy of his talent. In the end, he was reduced to making Demon Seed, a picture about a woman who finds herself at the mercy of a supercomputer.

Ridiculous though it sounds, the movie is in fact quite enthralling, thanks almost entirely to Cammell’s flair behind-the-camera. And while it might have been a slice of sci-fi hokum, at least Demon Seed empowered him to make the movie that’d rival Performance as his greatest ever creation.

The story of a husband and wife whose relationship is threatened by his serial killing, White Of The Eye is a film so transgressive, it’s hard to believe it was funded by an American studio. Not that the production company and the American censors didn’t try to scupper the completed picture. In the end, it took a letter for his A-list ally Marlon Brando to secure the film a certificate and secure Donald Cammell a place in the movie pantheon.

Featuring incredible, to-the-edge performances from Cathy Moriarty (Raging Bull) and David Keith (An Office And A Gentleman), White Of The Eye is all the more disturbing for Cammell’s claims that he was a sufferer of dissociative personality disorder whose alterative persona – nicknamed ‘The Uncensored Don’ – was capable of things he wouldn’t even contemplate in day-to-day life.

A man willing to point up autobiographical elements in a serial killer picture, it shouldn’t come as a surprise that Cammell’s third film failed to find a mainstream audience. Back on the film industry’s outskirts again, he was reduced to directing music videos and banal writing gigs. Then, when the chance came to direct a fourth film entitled Wild Side, the producers removed Cammell from the editing process and cut the picture behind his back. A depression set in that only abated in 1996 when the director put a gun to his head.

As an ending it couldn’t have been sadder, but to examine the life of Donald Cammell is to become familiar with someone who was always going to go out with a bang.